In my forthcoming novel, Monstrous Beauty, the character Ezra says, “I am scientific enough that I believe all difficult problems have a solution and yield to effort.” He said those words to a mermaid. Magic and science co-exist beautifully in fiction.

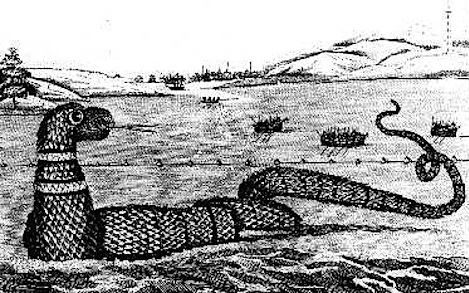

While creating my underwater world of dangerous mermaids, I read about the Gloucester Sea Monster—the most important, best-documented sea serpent you’ve never heard of—which was first mentioned in 1638, and last seen in 1962.

The beast’s heyday was between 1817 and 1819, when hundreds of people saw it in the Gulf of Maine—many more than have claimed to see the Loch Ness Monster and the Lake Champlain creature combined. Once, “a cloud of witnesses exceeding two hundred” watched it, at various angles and altitudes from shore, for three and a quarter hours. In the summer of 1817, the animal lingered so long and often in Gloucester that, “Almost every individual in town, both great and small, had been gratified at a great or less distance with a sight of him.” Families saw it; sailors; captains; whalers; and even a couple of naturalists saw it. Men shot at it with rifles and tried to impale it with harpoons. It seemed impervious.

In August of 1817 the New England Linnaean Society decided to conduct an investigation, noting:

It was said to resemble a serpent in its general form and motions, to be of immense size, and to move with wonderful rapidity; to appear on the surface only in calm, bright weather; and to seem jointed or like a number of buoys or casks following each other in a line.

A dozen or so witnesses were deposed in sworn statements. The serpent’s motion was “vertical, like the caterpillar,” according to Matthew Gaffney, the ship’s carpenter who shot at it. The head was as large as a horse’s but with a smaller snout, like a dog’s, or like a snake’s with a flattened top. The length was estimated at between sixty and one hundred fifty feet, and the diameter as thick as half a barrel, or a cask. Robert Bragg said the color was “of a dark chocolate,” although as the years went on the creature’s patina seemed to age to black.

In August 1818, a Captain Rich harpooned the sea serpent: “I hove the harpoon into him as fairly as a whale was ever struck.” The animal took one hundred-eighty feet of warp before the harpoon drew out, to the crew’s “sore disappointment.” Three weeks later, still chasing the elusive monster for profit, they wrestled a giant fish to its death and presented it on the beach as the sea serpent, only to discover that it was a very large “horse mackerel,” now called a Bluefin tuna.

Brain science is as magical as monsters. Humans see organized patterns and objects, and make inferences when the picture is incomplete or parts are hidden. Stimuli that are close together or move together are perceived to be part of the same object (global superiority effect). We complete edges where there are none (illusory contours). These highly-evolved tools of perception—essential for our survival—suggest how a person could see a long, sinuous, animated object and infer from it “giant serpent.”

But what did they see? Something unusual was in the water—something that looked remarkably like a sea serpent to a visual cortex primed to expect one. Yet the eyewitnesses were careful to rule out objects they were familiar with: a long rope of intertwined seaweed, schools of fish, or porpoises swimming in a line.

Magic was moving me: I was beginning to believe the tales. And then I saw a video called Saving Valentina about a humpback whale being cut free from the fishing nets that had entangled her. I searched the web and found photographs of whales trailing hundreds of feet of rope and debris. I read about drift netting and the threat to whales before its ban in 1992. I looked back at the testimony and realized that the witnesses gave the answer themselves, hidden in the plain language of their own descriptions:

“ like a string of gallon kegs 100 feet long.”

“He resembles a string of buoys on a net rope, as is set in the water to catch herring.”

“The back was composed of bunches about the size of a flour barrel, which were apparently three feet apart—they appeared to be fixed but might be occasioned by the motion of the animal, and looked like a string of casks or barrels tied together ”

If it looks like a string of gallon kegs, maybe it is a string of gallon kegs? And more,

“ [he appeared in] exactly the season when the first setting of mackerel occurs in our bay.” [Whales eat schooling fish like herring and mackerel.]

“ claimed he’d seen a sea serpent about two leagues from Cape Ann battling a large humpback whale.” [Proximity of a whale to the serpent.]

“At this time [the creature] moved more rapidly, causing a white foam under the chin, and a long wake, and his protuberances had a more uniform appearance.” [The foam suggests something is pulling the object, and the strand of kegs elongates when towed.]

“ the times he kept under the water was on the average of eight minutes.” [Like a whale.]

In the early 19th century a purse seine net would likely have had cedar or cork floats. But after a bit of research I found that small wooden casks were used as buoys and as floats for fish nets in Newfoundland and Norway in the 1800s.

Ezra would be pleased: A possible scientific solution had yielded to my effort.

Between 1817 and 1819 (more likely much longer) I believe the “sea serpent” was in fact the same poor humpback whale, entangled in a net or rope lined with keg or cork buoys, migrating to the Gulf of Maine every summer, powerful enough to survive the massive drag of its entanglement, and even to submerge the length of its torment into the depths with it, giving the illusion of the snake sinking. It’s likely that just by chance, the first keg or buoy in the line was different than the others, or was made of multiple objects lashed together, to create the illusion of a head raised above the body.

Monica Pepe, the Project Supervisor at the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society in Plymouth, MA, confirmed that there have been many long-term entanglements, citing a North Atlantic right whale named “Necklace” who had a fishing net wrapped around her tail stock for a decade. In most contemporary instances, disentanglement teams try to free the animals, but according to Ms. Pepe, “If it doesn’t appear to be life threatening they usually will try to let the animal free itself.”

Perhaps the “sea-serpent” whale eventually freed itself. But given very similar sightings well into the 1830s (after which the descriptions are more varied), I believe instead that it spent its life inadvertently bringing science and magic together along the shores of New England.

Bibliography:

O’Neill, J.P. The Great New England Sea Serpent: An Account of Unknown Creatures Sighted by Many Respectable Persons Between 1638 and the Present Day. New York, NY: Paraview, 2003.

Report of a Committee of the Linnaean Society of New England Relative to a Large Marine Animal Supposed to be a Serpent Seen Near Cape Ann, Massachusetts in August 1817. Boston, Mass.: Cummings and Hilliard, 1817.

Wolfe, Jeremy M., et al. Sensation and Perception. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, 2009.

Elizabeth Fama is the author of Overboard and the forthcoming Monstrous Beauty. She holds a BA in Biology with honors, an MBA, and a PhD in Economics and Finance.

Very interesting article! Thanks.

Your thesis sounds very believeable. Twisted seine nets can appear like solid, scaled bodies from a distance when wet. I’ve seen the phenomenon.

Why try to wrap myth with a veneer of plausibility? It is so much more fun when you don’t understand it. It is the thrill of the unknown that lured so many of us to sea…

@3: I think it’s a difference in the curious nature of the individual. For some, it’s much more fun and stimulating to the curiosity and imagination of a person if it is an unexplanable myth. Other people continually seek to understand and explain. So to the latter type of person, it goes beyond “myth”–here is a phenomenon with many confirmed and documented sightings, when we know of no such creature existing. It might be explained in just the way this article has done.

I find that “creatures” like Nessie and Champ (and this one) are interesting in that the only thing that precludes them from being a giant serpetine water animal is that we don’t see more of them, or capture/kill any, or find any bodies washed up on shore. This either makes them a magical or mystical creature, or some other phenomenon that remains unexplained. For example, if one were to see a whale (and confirm it as a whale), it could be an awe-inspiring experience, but it wouldn’t generate mystique and interest from a whole town or country. People have seen tons of whales, we know what a whale is, so it’s no big deal. If we see a serpentine see creature, on the other hand, that is an animal that we have no knowledge of. If we cannot confirm it as a living animal of unknown classification (by touching it/petting it, interacting with it, or dissecting it) then for some people it becomes a magically elusive creature. For others, there is no evidence that such a creature exists, and so they must needs seek the actual explanation of the sighting.

Fascinating post, Elizabeth! My midgrade WIP is about an amateur forensic scientist with cryptozoolgist parents, so these sound like explanations she’d come up with for the things her parents are investigating.

Looking forward to MONSTROUS BEAUTY!

Interesting article! While I don’t think this theory explains all of the sightings, I certainly find it fascinating!

I saw this thing myself – in the mid-1990’’s . It exists and it’s not a net. I was fishing on the breakwater in Gloucester. It exists! But you have to see it with your own two eyes to believe it.